© Iain Brown

© Iain Brown

Our clients are everything

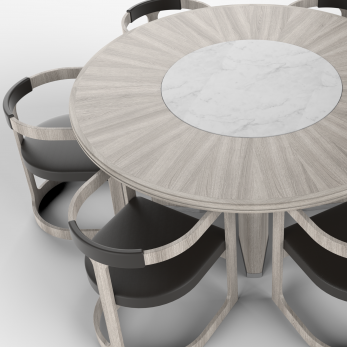

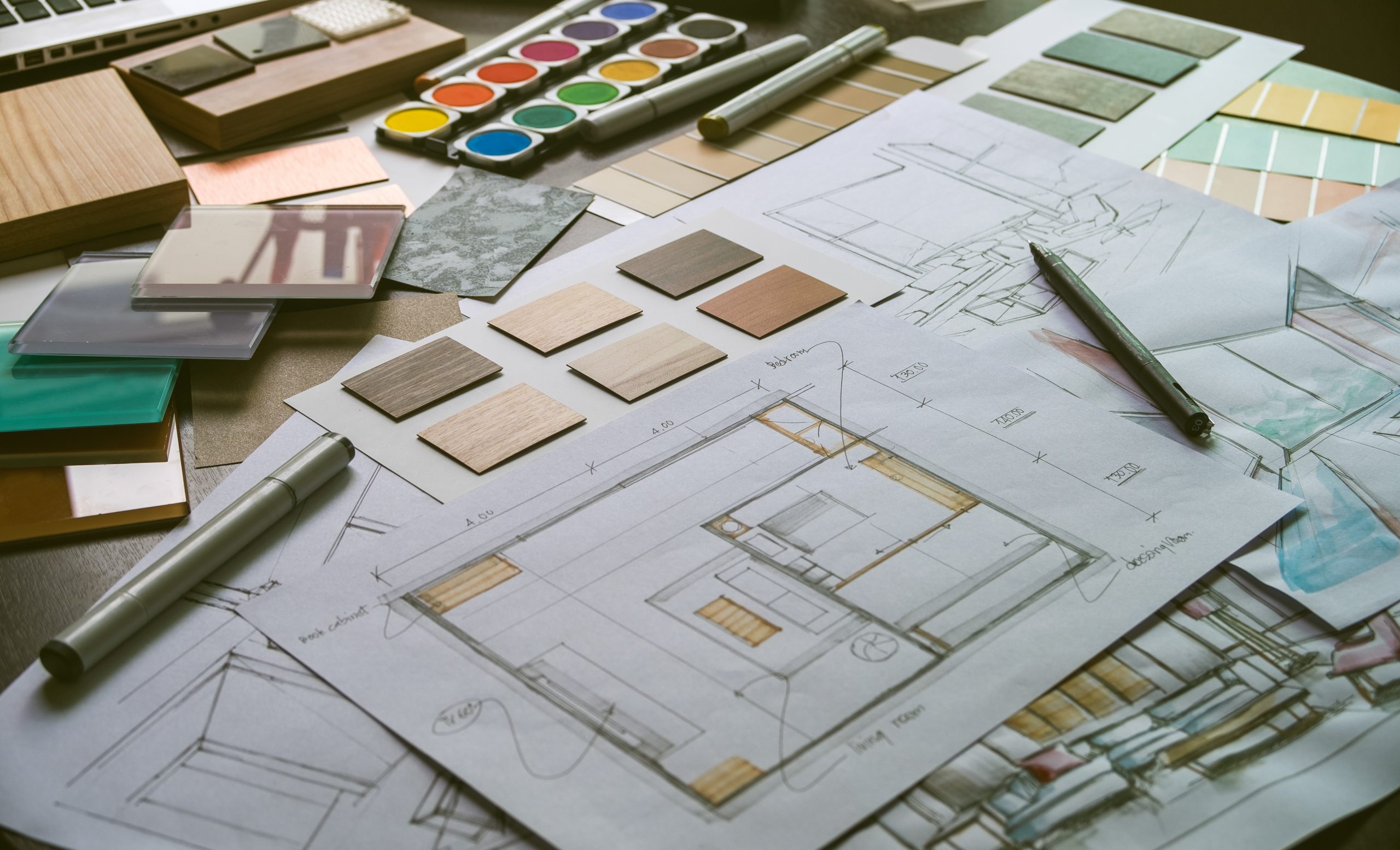

Whether it’s a private commission to bring your personal idea to life, a corporate brief to meet a detailed specification, or a request from a public body to restore an architecturally sensitive interior, we offer the expertise and creativity to surpass your expectations.

Our team, inspired by the family values of our founders Michael and Susan Mancini, takes immense pride in the expressions of delight and amazement when clients unveil a commission for the first time. We are here for you every step of the way, from the initial drawings, through the design and construction, to the delivery and fitting of the finished furniture.

Discover more